What is an intelligent agent

The fundamentals of an intelligent program.

What is AI?

Not in the philosophical sense, “Can only humans think? Is AI about making machines act like they are thinking? Or does thought transcend the human species, and biological organisms?”

No. I mean the practical definition. What is AI for someone trying to solve a real-world problem?

In practice, AI is a set of design principles for building successful systems that can be called intelligent, where ‘successful’ and ‘intelligent’ are left for you to decide. Those systems are known as intelligent agents.

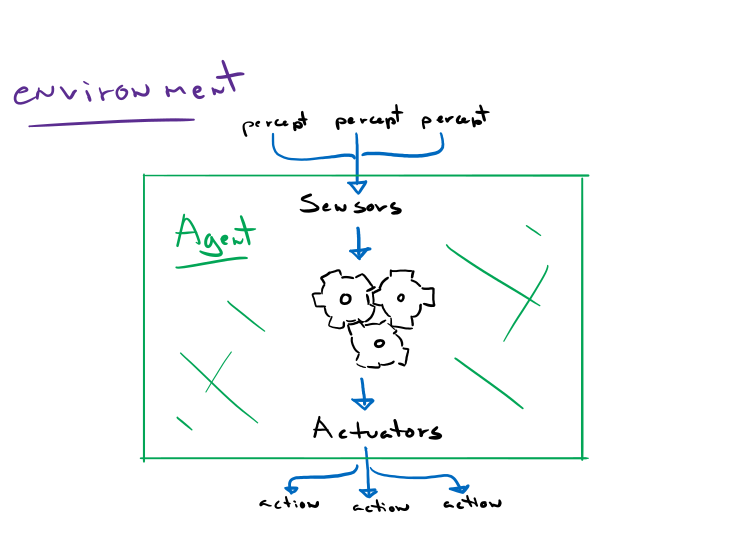

An agent is anything that can be viewed as perceiving its environment through sensors and acting upon that environment through actuators. Think of a robot for example as the agent, the cameras, microphones, thermometers are the sensors, and the stepper motors controlling the robot’s various components are the actuators.

The environment could be anything you define to be relevant to the agent. It could be the actual world we live in, or it could be a small set of states. It’s the part that percepts come from and actions sent to.

The agent will rely on the percepts perceived by the sensors and its own built-in knowledge base to decide what action to take. It may have to analyze its entire percept sequence to make an intelligent decision. This mapping from percepts to actions is what’s known as an agent function.

The simplest agent implementation of this agent function is to hard code all possible combinations of percepts and all possible combinations of sequences of those percepts and manually assign an action to each one. This implementation of the agent function is called an agent program. It is one way to implement the agent function. Actually, it’s a terrible way to implement an agent function for any nontrivial problem, but it is a valid agent program.

In fact, the discussion of various ways to implement various agent functions is at the core of this site. But before we start solving problems using intelligent agents, we must first fully define the problem.

The task environment and its properties

The task environment is essentially the problem that our agent is trying to solve. For example, if we were building a self-driving vehicle, we would specify it as such:

| Agent | Performance Measure | Environment | Actuators | Sensors |

| Self-driving vehicle | Safe, legal, comfortable ride, minimize fuel consumption, maximize time efficiency. | Roads, other vehicles, pedestrians, debris, wildlife, weather. | Steering column, engine throttle, brake cylinder, signals, horn. | Cameras, radar, speedometer, GPS, engine sensors, microphones. |

The performance measure is what describes good scenarios and what we want our actions to lead to. In our example, some desirable qualities for the self-driving car are to be safe, legal, comfortable, etc. Note that some desired qualities conflict (such as ‘safe, yet fast’), so the agent will need to find means to maximize time efficiency without putting us in danger.

The environment in our example is anything that our vehicle would care about. The roads, other vehicles, pedestrians, wildlife, the weather, etc. Note that elements of the environment may be simple objects (e.g. road debris), but it may be other intelligent agents (e.g. other vehicles).

And finally, the actuators and sensors are the different components that let the vehicle interact with the world.

The range of task environments that might arise in AI is vast, but they do tend to share common properties which we can use to categorize environments. Once an environment is categorized, we can pick known algorithms that are suited to solve them or we can build upon a family of existing techniques.

1- FULLY OBSERVABLE vs. PARTIALLY OBSERVABLE

If an agent’s sensors have access to the state of all the relevant elements at all times, then it is a fully observable environment. On the other hand, a partially observable environment has access to a portion of the states of the environment. Fully observable environments are easier to handle as you do not need to maintain a record of states and infer probabilities of states of relevant components. You might even have an unobservable environment which can still be solved (with increased difficulty) if you have a way to measure performance.

Examples

Observable: [Chess] – The agent knows precisely where each piece is located, who owns it, who’s turn it is and the agent has access to this information at any point in time.

Partially observable: [Self-driving vehicle] – The agent has complete access to some of the information such as the current speed, a view of its immediate surrounding, weather conditions, road conditions, but it does not know if another vehicle is approaching around the corner, or what traffic is like a few intersections away.

2- SINGLE-AGENT vs. MULTIAGENT

Are other agents involved in the task environment? In a sudoku puzzle, no. But in a game of chess; absolutely. Simple enough, but sometimes it may not be clear if some elements of the task environment should be agents or simple objects. For example, in the self-driving vehicle environment, other vehicles are also agents. But what about pedestrians? Animals? Or fire hydrants?

For that, we observe the performance measure of those elements. Other vehicles have the same desired outcome of ‘safety’, and thus, working together to ‘not collide in one another’ is for each other’s benefit. Our agent and other vehicles form a cooperative multiagent environment. In turn, when two elements work towards maximizing their performance measure minimizing the other elements performance measure, such as in a game of chess, it is known as a competitive multiagent environment.

3- DETERMINISTIC vs. NONDETERMINISTIC

If the agent is aware with absolute certainty of the effects of all its actions on the environment and the following state, given any current state, then it’s a deterministic environment. But if the agent does not know with certainty what might happen next, it is a nondeterministic environment. Some textbooks will refer to the word ‘stochastic’ as a synonym for ‘nondeterministic’. Furthermore, some textbooks will make a distinction between ‘stochastic’ and ‘nondeterministic’ and define a task environment to be ‘stochastic’ if it explicitly deals with probabilities. (“There is a 60% probability of a collision given X” vs “This action might lead to a collision”)

Examples

Deterministic: [Chess] – The agent knows precisely what actions it can take and their consequences. It also knows of all the actions the competing agent can take and their consequences.

Nondeterministic: [Self-driving vehicles] – Just like most real-world problems, the agent never really knows how the vehicle will react when controlled. The brakes may malfunction, the engine may seize, the tires may slip. The agent is able to make good predictions, but not with absolute certainty.

4- EPISODIC vs. SEQUENTIAL

In an episodic task environment, the agent’s decisions are based on the present percepts. They are not influenced by past states or decisions and will not impact future states nor decisions. Think of a facial detection AI. Every image fed to the AI is an atomic event that is not influenced by previous images nor future ones. In contrast, a sequential environment has long-term consequences for present decisions. Sequential environments add another level of complexity because the agent now needs to look ahead before taking an action.

5- STATIC vs. DYNAMIC

Can the environment change while the agent is processing? If so, it is a dynamic environment. A self-driving car’s environment will constantly change in real-time whether the agent has deliberated an action yet or not. Time is of the essence. In a static environment, time essential stops while the agent is thinking. For example, in chess, the state of the board will not change until the agent takes an action. It is not to say that time is not part of the environment. It can and likely will be part of the performance measure. Swordfish (the leading chess agent), will search about 20-30 flops (half moves) ahead to satisfy its ‘time’ performance measure.

6- DISCRETE vs. CONTINUOUS

This property refers to the range of values the agent’s percepts, actions and states can hold. In the chess example, each percept, state, and action are distinct and finite. This is known as a discrete environment. In contrast, a self-driving vehicle’s percepts are continuous (speed, time, video feed, audio feed, etc.) and so are the actions (steering column angle, pressure on the engine throttle, etc.). Even the environment itself is continuous (with respect to time). The self-driving vehicle agent is part of a continuous environment.

7- KNOWN vs. UNKNOWN

Although it is a property of the task environment, known and unknown task environments refer to the agent’s knowledge of the environment. You can think of it as ‘understood’. An environment might be a fully observable environment, but completely unknown. For example, an agent interacting with a game whose rules are unknown. The agent is usually forced to experiment and learn the rules given some performance measure. In contrast, in a known environment, the consequences of each action are known (or the probability of a consequence in a stochastic environment).

Summary

Those are the fundamental properties of the task environments. It is interesting to note that the hardest problem to solve with intelligent agents is one that is partially observable, multiagent, nondeterministic, sequential, dynamic, continuous, and unknown. This almost perfectly describes the self-driving vehicle agent (except for the unknown; the consequences of our actions are known), yet, engineers all over the world are making great progress in this field!

Examples (omitted known/unknown as it depends on implementation):

| Task Environment | Observable | Agents | Deterministic | Episodic | Static | Discrete |

| Chess | Fully | Multi | Deterministic | Sequential | Static | Discrete |

| Poker | Partially | Multi | Stochastic | Sequential | Static | Discrete |

| Image analysis | Fully | Single | Deterministic | Episodic | Static | Continuous |

| Refinery controller | Partially | Single | Stochastic | Sequential | Dynamic | Continuous |

Now that we have discussed different types of agent environments, we delve into the last section of this article.

The different types of agent programs

The agent program (alongside the agent architecture) is what we are really interested in. It’s the solution to our problem. In fact, designing agent programs is at the center of modern AI. They typically follow this simple structure: a percept comes in, the program is executed, and an action comes out (‘do nothing’ is a valid action). Note that contrary to the agent function, the agent program will only take one percept at a time to process.

There are four basic types of agent programs.

1- Simple reflex agents

The simplest kind of agent is the simple reflex agent. These agents select actions on the basis of the current percept, ignoring past or possible future percepts.

Note that the ‘interpreter’ in our example is purely conceptual. It may be implemented using logical gates (e.g. a vending machine), neural networks with activation functions used to match percepts to an interpretation, or just ‘if – then –’ clauses.

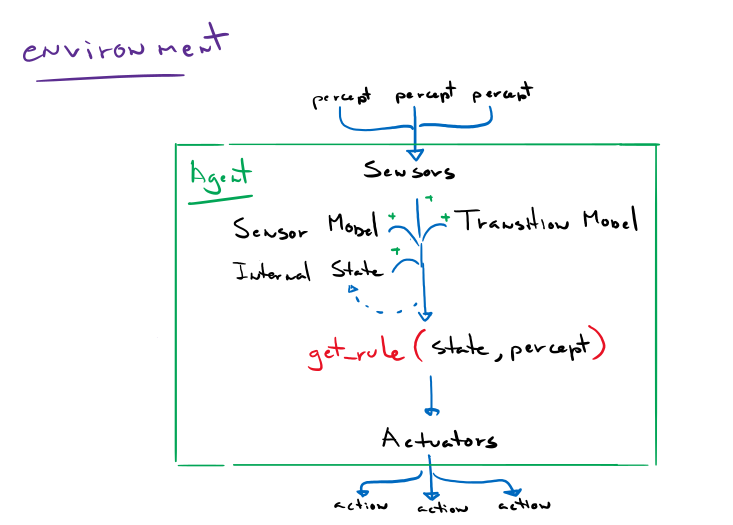

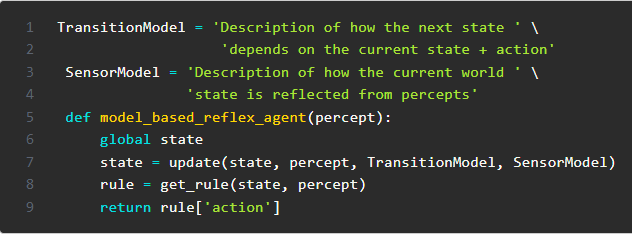

2- Model-based reflex agents

In some situations, a simple if – then – approach is not enough. An agent may find it beneficial to act differently given the same percept at two different points in time. For example, if someone offers you water, you may or may not accept it depending on your current thirst levels. The model-based reflex agent adds an internal state to the agent. ‘If water is offered and state is “thirsty”, accept water’. Additionally, the model-based reflex agent keeps track of previous percepts. This is particularly helpful in a partially observable environment. The agent now has access to historical data to reference upon for some of the currently unobservable aspects of the environment.

Updating its internal state and the state of objects/agents around it requires two kinds of knowledge to be programmed into the model in some form. First, the agent needs to know ‘how the world works’, ‘how the world changes over time’. For example, a self-driving vehicle needs to know what happens when it opens the engine throttle or turns the steering column. This is called a transition model. Second, the agent needs some information about how the state of the world is reflected in the agent’s percepts. Or in other words, ‘how to make sense of the world it sees’. This is called a sensor model.

Together, they allow the agent to keep track of its state, the environment, and other objects/agents.

3- Goal-based agents

Knowing the current state of the environment is not always enough. Take chess for example. Knowing the rules of the game is not enough to succeed. You also need ‘goal information’ in this scenario which describes a desirable situation. Such as “don’t lose the king” or “get the opponent’s king”. This type of agent can easily be combined with a model-based agent with the difference being in the decision-making process. Where the model-based agent will map a state and percept to an action, the goal-based agent will decide on an action based on which action (or sequence of actions) will help achieve a goal. And so, a goal-based chess agent can sacrifice its own piece to protect its king not because this behaviour was mapped, but because it is the only action it predicts will achieve its goal of not losing the king.

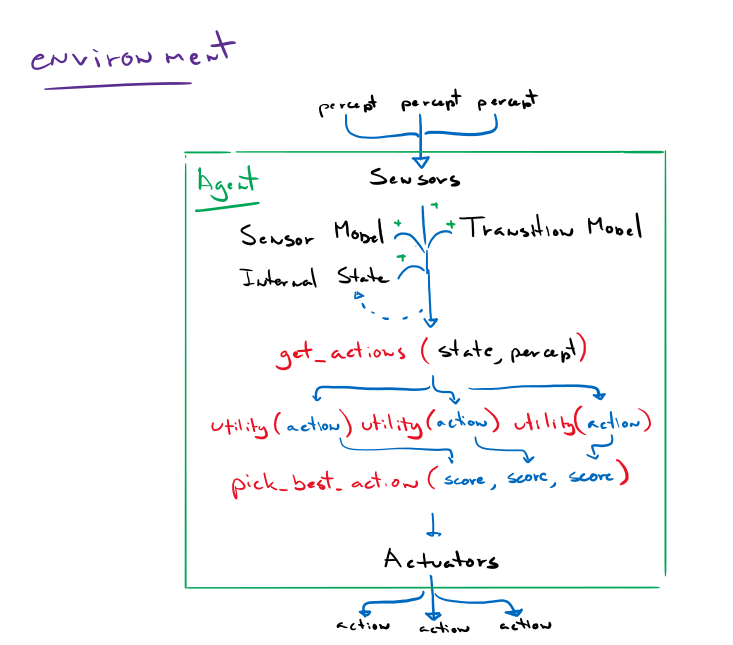

4- Utility-based agents

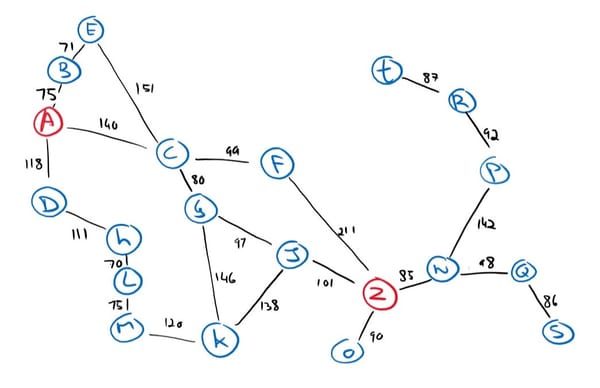

Sometimes, achieving a goal is not enough. Sometimes we want to achieve said goal faster, cheaper, safer, reliably, etc. Think of google maps; we don’t want just some route to our destination, we want the best route to our destination. A goal-based agent will happily take you on a journey around the country as long as it gets you to your destination eventually.

What this agent type adds is an implementation of the performance measure called the utility function. It will weigh and balance all our desired qualities and rank a scenario. This is particularly helpful when we have conflicting goals (such as a ‘fast’ yet ‘safe’ self-driving vehicle), the utility function specifies the appropriate tradeoff. Second, when there are several goals that the agent can aim to achieve, the utility function can pick the path with the highest probability of success or importance. Or both.

And this concludes our lesson about intelligent agents. Next, we will learn about solving problems by searching.